Formula 140

Formula number 140 in the ole Darkroom Cookbook is a nice basic paper coating solution.

a sensitizer for all seasons

The recipe makes like enough for three years, and well - I usually move more often than that, so I've started making up 8oz or 250ml amounts. Why 250ml? It's the amount that my handy-dandy amber Boston bottles hold. It's also convenient that it doesn't cost a month's salary in silver nitrate to mix up a smaller amount. Ahh to be a darkroom nerd in the 90's when silver was cheap.

My scaled version of warm printing out paper sensitizer

- 21g Ferric ammonium citrate, green

- 3.5g tartaric acid

- 8.75g silver nitrate

- 250ml of distilled water

I originally made up around 100ml of this to save on silver nitrate. By goodness, 100ml lasted a year. I just finished off my first batch and it has been as good as the day I mixed it the whole time.

I've coated a bunch of different paper types with this.

Right now, I've got a batch of mulberry fiber paper drying that I'll be printing with 5x7 litho negatives this week.

More to come

Goodbye to Fujifilm

As I put the last strap of packing tape on the freshly store bought 12 x 12 x 14 box I’d picked-up earlier that day at lunch, I was taken back to a moment of afternoon summer reverie. For an instant, I was 25 again reveling my first new camera: a Canon Rebel XT and a 24mm lens. At the time, I ran the shipping department for an odd little store in downtown Portland that sold roof racks. My life was spent in boxes and tape dreaming of photographic adventures.

One hot summer week it arrived. My mid-year bonus had gone to pay for it and the B&H Logos on the strapping tape made me giddy. As a fellow shipping expert, it also made me a bit jealous. I remember my co-workers being aghast at how much I’d just spent at once, on cameras of all things. I knew it wasn’t going to be the last time.

Fast forward to 2024, and I found myself again amidst boxes and tape on a summer afternoon. This time, carefully wrapping up each lens in it’s own bubble wrap swaddle, and then shoving it into the box hoping to god it doesn’t bust open mid-shipment. I don’t ship nearly as much as I used to, but I still take a bit of pride in my ability to get things to their destination nicely. I feel like that’s how you respect both the equipment and the purchaser: take care of it like it’s worth a million dollars.

After about eight years of being a Fuji fanboy, it’s time to send those beautiful machines on to their next adventures. The X-T3 and 50-140mm will always remain one of my favorite camera+lens combinations, but I’m excited to see what nearly a decade of improvements in mirrorless technology have brought. On a sentimental side, it’s fun to now be part of the camera gear ecosystem, passing my used equipment down to the next user. Any time I get a vintage piece of equipment I like to imagine all the lives it has lived before me. I hope that my gear has lived an exciting life with me, and will go on to many more adventures.

Looking back over the years I’ve been lucky enough to shoot quite a few middle range consumer and pro-sumer grade cameras. It’s been fun, but it’s time for us to move on up in terms of digital real-estate. Nothing massive mind you, I’m not jumping to medium format yet. However, the full frame Nikon Z6iii has all the video features our X-T3 lacks, plus it has my all-time favorite feature: a flippy screen.

We’ll see how I get along with the Nikon, the last Nikon digital I shot was a D600 in 2016, and honestly the images blew me away. Hopefully, I’ll get the same tingly feeling from the Z6iii once it arrives.

Until then, maybe we’ll shot some film this weekend.

Sailing in Summer: A windy Saturday

I got a message recently asking whether, “if the storm warnings lift,” I’d like to come crew a small sailboat on the Columbia river for a short race. Now, when I hear someone ask if I want to come help race – my ears perk up. However, racing since I have almost zero experience as a sailor, I replied “Sure, as long as I can bring a camera and be ballast.”

For a moment it seemed as if the race was going to be cancelled, our planned afternoon sail turned into a booze-cruise, but then we all got a note that the race was back on. Winds were going to be strong, but we hit the water with the anticipation of competition.

I was the fourth person on the boat, sitting in the middle sloshing side to side at every tack. I also had the pleasure of being in charge of the boom vang and out haul. Which, for all their fancy sounding names are really just ropes. The key part of being in the hold, I had a nice vantage point of all the gents I sailed with.

Video from Saturday Sail

The three gentlemen who I joined on the boat are all much more experienced sea-hands than I. Cody and Matt have both been sailing for a number of years, and Scott – the owner of Deadbeat, the boat we are crewing – has been on the water his whole life.

I met these three over 15 years ago when we all worked at a store in Portland which sold and installed roof racks and sporting carriers for cars. Scott and I ran the inventory and online order fulfillment, Matt and Cody sold and installed everything in the store. We were all in our 20s, and making bad decisions on the daily – but at work we came together and solved problems and made someone else’s day better. A kind of millennial trauma bonding, in a pre-covid world.

So, you might ask: what happened with that storm warning?

Thankfully we didn’t get rained on, but as the afternoon progressed the winds kicked up. Watching the water start to turn white across the river is always kind of exciting for me. I love the feel of the boat bobbing to and fro, and even love feeling the wind pull the boat horizontal while we scramble up the high side to dangle our legs off the edge.

One of the things that became immediately clear to me: sailing is all about communication. Being open to correction, clearly stating your needs, and addressing the next challenge rather than contemplating your last decision. One things for sure – I won’t have to think twice about going out again when the invitation comes.

Thanks Scotty for the invite, and thanks to Cody and Matt for keeping me safe.

Color photos: Fuji X-T3 + 50-140/2.8

B&W photos: Ilford HP5 – Leica IIIa + Summaron 35/3.5

A beach day

Wides images are on the M240 with the Chroma Camera 24mm, and the rest are on the M10 mostly with the 135mm f4 Tele-Elmar.

Chroma Camera Double Glass 24mm f11 - Every Lens for Every Occasion

I’ve been following Chroma Camera for a few years now, and have been really impressed with his design and production quality. I took most of 2022 and 2023 off from social media, but when I came back to Instagram recently it seemed like the Chroma Camera projects had been supercharged! A new website, a series of things to order, and – even an off-the-shelf ready to ship lens! A lens designed to fit on a camera that I own. I looked at the sample images, and added it to my cart immediately. Then, I slept on it. Read the thoughtful reviews from 35mmc and Kosmo Photo, looked at some of the images that Steve of Chroma Camera had been posting on film and decided I was smitten. I sent in my order and waited about a week for the lovely little piece of optics to arrive. I have been shopping for a wide angle or super wide angle for the Leica for probably 8 months. I’ve tried the 28mm TT Artisan, and it was okay optically – but didn’t feel particularly nice to use. Plus, it’s still only 28mm. I normally shoot at 35mm, so 28 isn’t as dramatic as it might be if I was a portrait shooter. Other affordable options? The Rokkor-M 28mm, lots of issues with those. The 28mm Fun Leader seems the most obvious comparison, and based on my research it looks like a fun lens. But, it’s three times the price of the Double Glass, and has a weird focus shift thing I can’t get over. So, I had narrowed my wide-angle search down to the Voigtlander 21mm 3.5 and I had even started to bank pennies when I saw the Chroma Camera Double Glass on Instagram. I’ve been shooting 24mm lenses since my first digital SLRs (Canon 10d + Rebel XTi – don’t miss those days) because it was close to the 35mm focal length on APS-c. Ever since I’ve had a soft spot for the 24mm focal length, whether on full frame, cropped, or film. I guess for me the 24mm Double Glass hits a sweet spot of nostalgia, simplicity, and price.Background: Nostalgia and Handmade-ness

The nostalgia of 24mm

On wide-angles, composing, and range finders

Okay – I’m newish to the Leica eco-system, so let me talk about composing and focusing on a range finder camera with a super-wide for a moment. Please settle in for a treatise on implementation of the scheimpflug principle and the inverse square law. JK – if you’re on a digital – use Live View or an EVF. Get real – that’s why you own a digital camera.

If you want to shoot on film – grab an external optical viewfinder. Voigtlander makes nice ones, and you can get vintage ones on the ‘bay all day long.

Alternatively – if I remember to place the spot I want most in-focus in the middle of the RF patch and try to hold the camera level – then I can usually capture something nice.

It’s a sort of shoot-from-the-hip kind of lens.

Build Highlights:

- L39/M39 on the back means that this lens can mount on almost anything.

- Sturdy 49mm filter threads on the front means it can take any filter or accessory you want to throw at it.

- A burly machined aluminum body means it’s threads won’t eat other accessories or fail to seat.

Lens mis-use and abuse

I think it’s reasonable to expect a decent performance out of a decent piece of glass, even when used in ways the designers didn’t intend.

Based on what I’ve read, the intent with this piece of glass was to make a nice snap-shooting focus-free lens that would provide sharp distortion free results. It’s a great piece of engineering for that.

What it wasn’t really designed for: extension rings, macro photos, studio close-ups.

But – being that this is such a well thought out compact lens, it sort of does lend itself to those sorts of uses if you’re constantly mis-using your lenses like me.

Macro Rings and close-up things

The day that my Double Glass lens arrived I also had a visit from my uncle who brought me a large crate of old camera stuff from an elderly friend. Inside that crate: a set of l39 extension rings.

It seemed like too much of a coincidence to not make use of them, so after a bit of cleaning to get the last 60 years of dust out of the threads I stuck the 10mm extension ring on there – flicked on live-view, and was pleasantly surprised.

The Letiz film cassettes arrived the same day as the extension tubes, making them an appropriate subject. The amount of sharp detail the lens gives is pretty surprising.

Adding a close-up lens to the front of this makes it a fun lens for all kinds of closer-up stuff. I love the extra distortion that you get outside of the center of the frame.

On shooting Digital

In all my mess of cameras I don’t have a screw mount or m-mount film body. So, I haven’t shot any film on this lens. To be honest, I likely won’t. I bought this lens specifically because I have a a later model full-frame digital body. The biggest factor for me: usable ISO range.

In the last couple weeks of shooting this lens I choose either auto-ISO or auto-shutter speed. Clearly, auto-shutter speed only gets you so far when you’re hand-holding, so the auto-ISO options need to be fairly robust.

This lens, with it’s fixed F11 aperture, still shoots pretty decently on my M10 at ISO 10,000 – I mean, would I use that image for work? Maybe not. Group-hangouts? Of course!

I leave that as my one caveat with this lens, I’ve not shot it on film. But – based on how it looks on digital I can only imagine it’s just as forgiving and quirky on film.

Is it everything for everyone?

Clearly, the answer is yes.

So long as your use-case requires a fixed-focus, fixed aperture, body-cap sized lens.

Is it really a niche lens that appeals only to the deepest of camera nerds? No, definitely not – I think if I was looking for something to put on an A7C or even an S5 this would be pretty sweet.

Is it only a tourist lens? This is definitely the lens I’ll have next time I visit central park. This is a perfect summer picnic party lens. And, it’s small enough to carry all day.

What about working with it? I’d definitely shoot a music video with this lens. I will most likely shoot some dance with this lens. Caveats? You want lots of light to work with it.

My favorite way to shoot it is to carry a +1 close-up adapter, making it a pretty dang small and versatile lens.

- Chroma Camera: http://chroma.camera

- Jason Lane: https://www.pictoriographica.com/

Around town with a German Kodak

It was a warm Sunday afternoon. We were full of tacos and horchata. The antique store beckoned me. My friend Art and I stepped inside and a musty old shop smell met my nose. All the yellowing newspaper and pieces of old leather scattered around told me that treasures were to be found.

After rummaging through old magazines and LPs we came upon a small glass case of photo related items. I spied a small brown folding leather case that was stamped ‘Made in Germany’ on the bottom. Always a good sign.

‘Mind if I take a look in here?’ I turned and asked the woman at the counter.

‘Sure, just close it up when you’re done hun.’

‘You bet!.

I moved about sixteen boxes of slides, and what I seem to remember was a tube tester or maybe it was a spark-plug sales road case, either way it was large and awkward. Once out of the way I softly peeled open the front glass door and reached inside to extract a tiny leather case stamped Kodak.

I’ve never really cared about Kodaks. As a long time thrifter I’ve seen too many Kodak Pony’s and Brownies and utter junk over the years that I’ve rarely taken a Kodak camera with much seriousness. However, somehow I’ve gone my whole life never using one of the old German Kodaks. Recently, however, I’d been curious.

As I unsnapped the back of the leather case I let the top half drop down and glimpsed a brilliant silver Retina logo emblazoned on a lovely red velvet lining. In my hand I held an utterly lovely Retina 1a in perfect condition. I felt around a little bit and found a button, pushed it – nothing. Then felt around a bit more and found a button on the bottom, bingo the front cover popped open and the always pleasing sight of a Compur shutter met my eyes.

A brilliant little Schneider Xenar 50mm f3.5 was nestled into the Synchro Compur shutter. I squinted in the dark antique shop and looked close, feeling the knurling in on my finger tips and breathed a sigh of relief as I saw the shutter speed plate was set to B. This camera had been owned by someone who knew what they had.

I looked at it, said to myself, ‘well that’s a funny little camera!’ Gave the film advance a tug, and felt the clickity little pawls ratchet away, and saw a tiny little wheel roll over on the front of the shutter, and then pushed the shutter release and it gave a little ‘snick’ and I was hooked. The stiffness in the focus concerned me at first, but I figured I’ve re-lubed a helical here and there why not this one?

The price was right, ‘can I pay cash?’

‘Cash is king!’

I took the Retina home. I’d like to say that my life is so rich and full of other activities that I forgot about it for years, and then recently on a cold rainy afternoon I found the camera hiding in the back of a closet. The smell of the leather case reminded me instantly of that warm sultry summer day all those years back.

But that’s not what happened, I obsessively shoved a roll of HP5 into it as soon as I could. I think I had film in it before I got home. I didn’t even run a lens cloth over it.

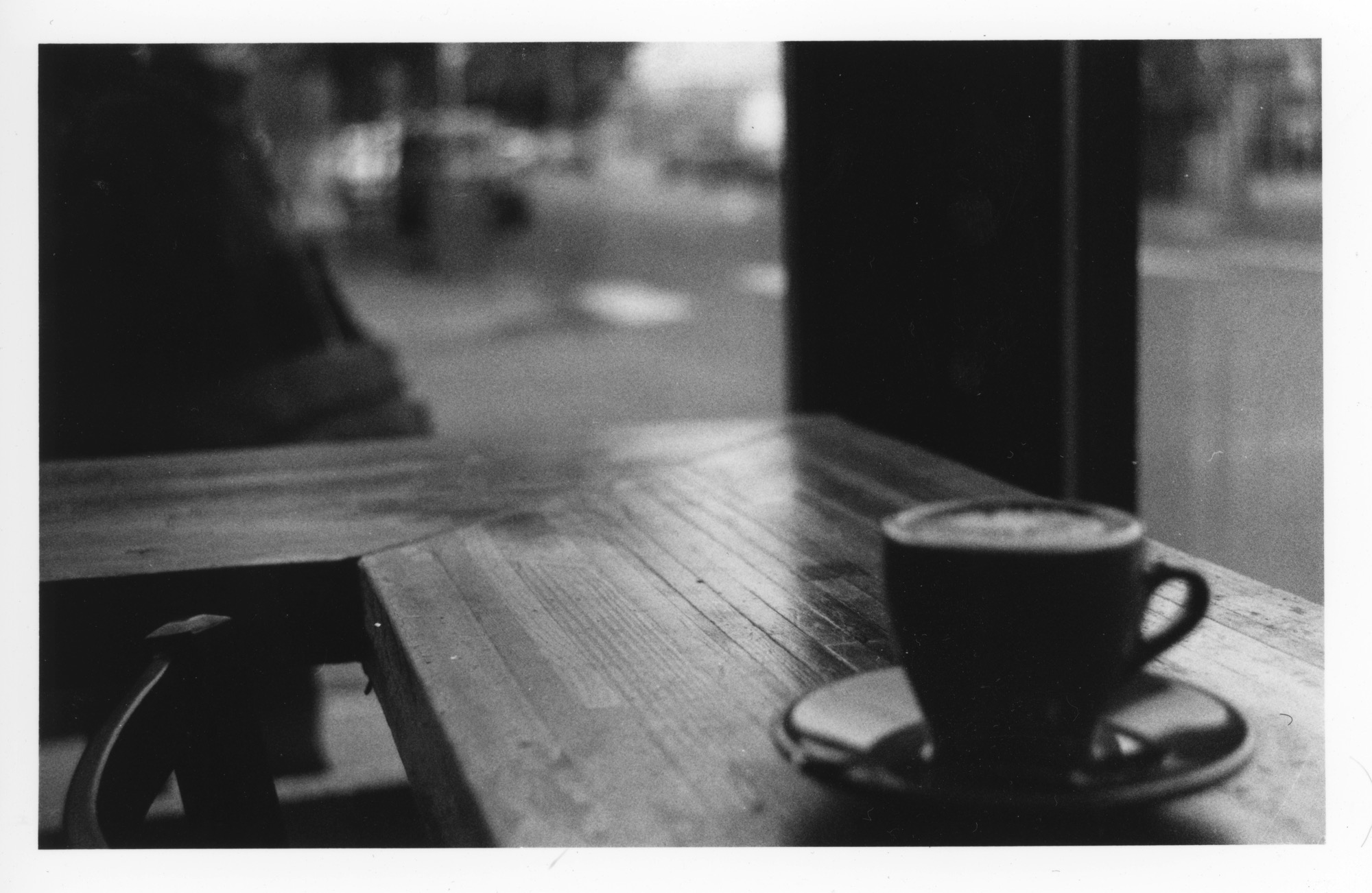

I always love the first raw, hazy test images that come out of antique camera finds. They are simultaneously thrilling and invigorating, and often slightly disappointing. But hey, that’s life right? Change happens. My eyes have gotten hazier over the years, makes sense that this old Xenar might have a bit of haze.

None the less, the images that came out of the soup for that first roll were really solid. Punchy blacks and bright whites. Not quite that special magic you hope to get out of some of these old lenses, but a nice sharpness with the feeling of more to give.

It’s a shutter with lens elements. This camera, the Retina and so many of these folders from the first half of the 20th century, are just simple cameras. It’s often a very over-engineered (or under-engineered in some cases) shutter, with a pair of lovely lens elements. Because of how simple the setup is, I was able to easily remove both the front and rear elements and give them a good cleaning.

After removing a thin layer of gunk from the inside of the rear meniscus and a ton of dust from the inside of the front element meant that when it all went back together it practically shined. Blowing out all the dust and snapping the shutter open on bulb, holding it up to the light. It looked gorgeous.

I loaded up another roll of HP5 and quickly worked through it. Impressed would be what I would say. The lens is really nice, it doesn’t blow me away, but I do like the rendering of older slow lenses and I love the absolutely tiny size of it. The images are good, they don’t make you swoon, but they do make you happy that you spent the time to use the camera. And when I say, ‘took the time’ I do mean that.

In a weird way, the cumbersome process of using the Retina 1a is what I love most about it. First, you have to open up the clamshell case, extract the lens, then I usually look at my hands for a few moments and think about how much I love holding well crafted objects. Then, I usually remember I have no idea how to use the Sunny 16 rule when I’m in the shade, and I pull out the meter on my iPhone. After taking a general reading of the approximate area I want to make an image of, I set the shutter and lens. Then, this is probably the best part, then you get to wind the film and charge the shutter.

With other cameras, like Nikons or Minoltas you’d instantly wind the film on and set the shutter. But, with a camera that won’t let you change to the fastest shutter speed after cocking the shutter you are better off waiting until you know what your image is going to be! The Retina 1a is one of those cameras – it goes all the way to 1/500th, which is nothing to sneeze at for 1951 – but you can only set it prior to charging the shutter.

Now is the moment you get to feel the little just-sharp-enough knurling on the film rapid winder, listening to the frame counter ratchet down, and feeling the film transport click away. It’s not the smoothest film transport, nor the most satisfying shutter to set – but there is something unique about the hand made practical nature of this affordable accessible old Kodak. It reminds me of the Contax IIa a little in this regard – simply a lovely object to handle and use.

Once your film is wound on, well now you just have to snap the shutter and you’re done! Oh, wait – unless you want to focus? How do you do that with a “view-finder” camera any way? Well, you could estimate – which I do quite a bit. Or, you could use an external rangefinder.

I pair my Retina 1a with a shockingly matchy-matchy Watameter rangefinder that I’ve owned for about 5 years, and it’s great. The Watameter has a nicely magnified viewer, and reads out in feet just like the Retina focus scale. I wish I could tell you that the camera view finder is a lovely thing to look through, but it’s not. It’s pretty small, tight, and cramped. This too reminds me of the Contax IIa.

So, what’s all the fuss? It’s a nice thing to hold in your hands. It’s a well thought out and well designed piece of machinery. It’s pretty. It makes nice images. It fits in your pocket. It reminds you that simple things can be the most fun.

The images in the gallery below are all from the Retina 1a, they are from the last couple weeks around home, and a visit to Skamania Lodge in Washington. The film is mostly HP5 developed in HC-110b and Fomapan 200 developed in, gasp, DF96. There is generous use of under exposure in some of the images. Weirdly, I kind of like it. I like how dark they can be and still have texture. Maybe that’s part of getting older.

Scarcity & Abundance on view at Around Oregon Biennial

I’m pleased to share that Scarcity & Abundance will be on view from August 3 – September 9, 2023 at the Arts Center in Corvallis, Oregon.

I am one of two film pieces that are in the show and I couldn’t be more pleased about it.

The contemporary arts ecosystem of Oregon was once known for its underground sensibilities – DIY aesthetics, experimental practices, craft, noise, and a unique lens for landscape. As many parts of the state struggle to remain economically viable sites for arts production and artist support, Around Oregon 2023 seeks to honor the artists holding fast to the previously described legacy. The selected artists’ works venture from traditional conceptions of their medium, and showcase Oregon for all that is strange, wild, and fighting to regrow.

-Ashley Stull Meyers, 2023 AOB Juror

A pretty little camera, Fujica 35-ml

Fujica 35-ml rangefinder camera, a 35mm delight to use and a treat to look at.

The older I get, the more I love estate sales. I used to go to thrift shops almost every day. Recently, at least here in Portland, I've noticed what used to be thrift store finds are now housed in glass at vintage shops marked up 500%. Because of that, estate sales are my new love. This particular camera came from an estate sale.

The camera was in decent condition when I found it, but the shutter was stuck and I had to open it up to give it a slosh cleaning in order to shoot some test rolls. The rangefinder was a bit out of whack too, which might have been why it sat unused for so long. Thanks to smart Japanese engineering rangefinder adjustment screws are easily accessed from under the cold shoe.

Fuji made a ton of rangefinders over the years, with a bunch of different medium format versions from 6x4.5 up to 6x9. However, the Fujica rangefinder line was not immensely popular in the United States, so they fly under the radar a bit. From what I understand the 35mm rangefinders, especially weren't sold in great numbers in the U.S. so they are kind of a treat to find in good condition.

Oddities of the line: they all have the wind lever on the bottom, focus wheel on the back, and rewind on the side. All these things, are exactly what I love about it. This, surprisingly, isn't the only rangefinder camera I own with a focus wheel on the back. The Mamiya Six folder I have also operates the same way (although it moved the film plane instead of the lens). I really love being able to focus with just the move of my thumb, it feels much more natural on a rangefinder for some reason.

The little camera has a 45mm f2.8 lens that is nice and sharp, a characteristic of pretty much every Fuji lens it seems. It is essentially a small view camera lens, threaded into a leaf shutter. You set the shutter speed and aperture on the lens rings, just like you would on your large format rig. This is, more or less, the basic set up of all the Fuji / Fujica rangefinders - slap a traditional leaf shutter lens on the front of a body and make it focus.

Some of the shots that I got from the camera are really lovely.

Performance documentation, stage 2 execution - What is a photo call?

Sometimes I'm shocked when I talk to performance artists and I suggest that we have a photo call to capture their documentation images and they look at my like my head just exploded. I'm relatively new to the theater community, but I've known about this as a process for documentation since my first theater shoot a few years ago.

Photo Call - the basics:

- Designers, directors, and others collaborate on a list of scenes they want photographed

- Production manager (typically) writes up a schedule to run through specified scenes in whatever order makes the most sense and shares this with the production team

- Actors, production team, and entire crew are called for a specific time and the scenes specified in the schedule are run through, allowing the photographer to capture them.

- Typically the photographer has the ability to ask the actors and crew to re-run scenes, or pose specific tableaus as needed to capture specific images.

- Photographer communicates what is and isn't working, and can adjust on the fly.

Why a photo call instead of straight production photos?

- Photo call allows the photographer to communicate with the crew and actors

- Allows the actors to just run through the scenes needed for images

- Photographer can get on stage, or much closer to the action than they would shooting a full run through

- Pausing action or at least slowing it down, especially in dark settings, leads to much cleaner photographs

- Photographer can move around without fear of disturbing your patrons

- More dynamic images can be produced

Why not just run the whole show for photographs?

- Time is money and the less time you need to have a photographer on site, or processing images the better you'll be on budget

- Simply shooting through a whole show without guidance from designers, directors, and others can generate a ton of images, but they will be a waste of space without some specificity as to what the team needs

- The temptation to run the whole show for photos easily slips into simply shooting when their is an audience, which goes back to problems that are noted above

Shout out to Brian Hashimoto who was instrumental in the creation of this text and for teaching me what a good photo call looks like.

Performance documentation, stage 1 planning

Work backwards from the end goal

I'm a big fan of identifying what you want to do and working backwards to accomplish it. Want to be sitting at the beach with a cocktail? Figure out how you're going to make it happen. Will you be on vacation? Will you be working? If you're on the beach, does it matter? So what does figuring out how to drink cocktails on the beach have to do with documentation? It's all about figuring out what you want, and how to get there.

Categorization of assets

Documentation end-use typically falls into a couple of different categories:

- Marketing

- Archival & Historical

- Reference

To get academic about it, I'd further categorize these with internal and external designations. Are materials being used internally by you, the artist, to come back to? Or are you using them primarily for external audiences for things like advertising. Thinking along those lines we can look back at our list as:

- Marketing (external)

- Archival & Historical (mixed internal/external)

- Reference (internal)

It's worthwhile to have these categories in mind when making your documentation plan. Some useful questions to ask yourself in the planning stages include:

- Is documentation required by your funding organization?

- Will you need to create promotional materials?

- Is this a final piece going into production, or in workshop and you will pick it up again later?

- Are you presenting your piece at a location, or at an event that is particularly noteworthy?

There are numerous things to think about in designing your documentation plan, but at it's heart simply asking yourself if you're needing internal or external assets will be a good start.

Internal vs External assets

As we noted above, the major differentiation between internal and external documentation assets will be whether you're using them for your own references, or whether you're generating promotional materials with them. While you might be able to use assets generated without this in mind, the acquisition tactics might be different based on your end goal.

Internal use assets such as a reference images from a workshop or rehearsal might be adequately captured on a GoPro mounted in front of your rehearsal space. Since you're the primary user of that footage, it all depends on what you want to do with it. If you just need reference material for a dance rehearsal, basic capture on your own might be just what you need.

Mixed use assets would require a slightly different approach than purely internal reference material. Your static GoPro camera that captures everything easily, and allows you to review footage at the end of the day might not be sharp enough for archive quality, and it might be so wide that it distorts the scene too much. Having a photographer attend a rehearsal session might be more reliable way to ensure you are getting images that can both be referential and used externally.

External use assets are typically designed in a more polished way. Unless you are specifically creating process images for social media use (which many artists are doing now) you'll likely want to capture images with full tech, costume, and in a complete set. Typically this means that you'll be bringing in a video person and / or a photographer to capture images during tech rehearsals. Many theater companies have a specific photo-call where actors are in full costume, and the production manager quickly runs through a specific set of scenes that the artists want to capture. Beyond photo-calls I've also worked with artists to stage photography outside of the theatrical space in order to develop purely marketing related images.

The planning process

I would definitely suggest you look at your documentation plan before you get too deeply into the creation process. There is nothing worse than waiting until closing night to try and get documentation for a project. Your crew, actors, and designers don't want to delay strike, or stay late on closing night for photos. Plus, if you wait until the end of your run to get professional images captured, you can use them for any promotional purposes.

If you need to develop marketing materials, you'll want to either design and stage images or video that can be used before you ever get to the tech rehearsal point. That mean's you'll need to work with a photographer or video person to come up with a concept, and shoot those pieces while you're in rehearsal.

If you can wait until tech rehearsal starts to generate final images, or promotional pieces I would suggest you book a photographer or video person early for your tech run. That way you they can watch the piece first, find out where the image needs are, and be sure they can capture them best based on the space and your requirements. Let them come watch a full-length run through so they know what to expect.

If your primary goal is to capture reference material for yourself then you can be a bit more relaxed in your planning process. However, I will say, it's good to have a plan and stick to it. If you are bringing a simple video camera into rehearsal every day do it every day. Make it part of your process, that way you won't have to think about it when you run out the door every day. Alternatively if you are bringing in a photographer for a workshop, either let them have free reign to capture images ad hoc, or provide them a set of guidelines of what you want to achieve with the images personally.

The purpose of creating a documentation plan is that it lets you create a budget for those materials. When I say budget, we aren't just talking money. Everything you commit yourself to takes time, and the more things you decide to do on your own, the thinner your time will be stretched. If you're directing a piece and plan on also taking photos, and creating a promotional video for it, keep in mind that the more time you work on those pieces the less time you'll be able to dedicate to the final theatrical performance.

In addition to that, many funding organizations require documentation. To make it easy on yourself you'll want to add documentation into your budget at the outset, and have a clear idea of what you want to deliver to the funding organization.

Write down some goals

If you've gotten this far, you're probably already thinking about what you want to do with your documentation and that's great. Grab a pad of paper and write down some goals, even if they aren't things you think you'll ever achieve it's good to know where your head is at.

Next time: Performance documentation, stage 2 execution and what is a photo call.

Shout out to Brian Hashimoto who was instrumental in the creation of these ideas.