Around town with a German Kodak

It was a warm Sunday afternoon. We were full of tacos and horchata. The antique store beckoned me. My friend Art and I stepped inside and a musty old shop smell met my nose. All the yellowing newspaper and pieces of old leather scattered around told me that treasures were to be found.

After rummaging through old magazines and LPs we came upon a small glass case of photo related items. I spied a small brown folding leather case that was stamped ‘Made in Germany’ on the bottom. Always a good sign.

‘Mind if I take a look in here?’ I turned and asked the woman at the counter.

‘Sure, just close it up when you’re done hun.’

‘You bet!.

I moved about sixteen boxes of slides, and what I seem to remember was a tube tester or maybe it was a spark-plug sales road case, either way it was large and awkward. Once out of the way I softly peeled open the front glass door and reached inside to extract a tiny leather case stamped Kodak.

I’ve never really cared about Kodaks. As a long time thrifter I’ve seen too many Kodak Pony’s and Brownies and utter junk over the years that I’ve rarely taken a Kodak camera with much seriousness. However, somehow I’ve gone my whole life never using one of the old German Kodaks. Recently, however, I’d been curious.

As I unsnapped the back of the leather case I let the top half drop down and glimpsed a brilliant silver Retina logo emblazoned on a lovely red velvet lining. In my hand I held an utterly lovely Retina 1a in perfect condition. I felt around a little bit and found a button, pushed it – nothing. Then felt around a bit more and found a button on the bottom, bingo the front cover popped open and the always pleasing sight of a Compur shutter met my eyes.

A brilliant little Schneider Xenar 50mm f3.5 was nestled into the Synchro Compur shutter. I squinted in the dark antique shop and looked close, feeling the knurling in on my finger tips and breathed a sigh of relief as I saw the shutter speed plate was set to B. This camera had been owned by someone who knew what they had.

I looked at it, said to myself, ‘well that’s a funny little camera!’ Gave the film advance a tug, and felt the clickity little pawls ratchet away, and saw a tiny little wheel roll over on the front of the shutter, and then pushed the shutter release and it gave a little ‘snick’ and I was hooked. The stiffness in the focus concerned me at first, but I figured I’ve re-lubed a helical here and there why not this one?

The price was right, ‘can I pay cash?’

‘Cash is king!’

I took the Retina home. I’d like to say that my life is so rich and full of other activities that I forgot about it for years, and then recently on a cold rainy afternoon I found the camera hiding in the back of a closet. The smell of the leather case reminded me instantly of that warm sultry summer day all those years back.

But that’s not what happened, I obsessively shoved a roll of HP5 into it as soon as I could. I think I had film in it before I got home. I didn’t even run a lens cloth over it.

I always love the first raw, hazy test images that come out of antique camera finds. They are simultaneously thrilling and invigorating, and often slightly disappointing. But hey, that’s life right? Change happens. My eyes have gotten hazier over the years, makes sense that this old Xenar might have a bit of haze.

None the less, the images that came out of the soup for that first roll were really solid. Punchy blacks and bright whites. Not quite that special magic you hope to get out of some of these old lenses, but a nice sharpness with the feeling of more to give.

It’s a shutter with lens elements. This camera, the Retina and so many of these folders from the first half of the 20th century, are just simple cameras. It’s often a very over-engineered (or under-engineered in some cases) shutter, with a pair of lovely lens elements. Because of how simple the setup is, I was able to easily remove both the front and rear elements and give them a good cleaning.

After removing a thin layer of gunk from the inside of the rear meniscus and a ton of dust from the inside of the front element meant that when it all went back together it practically shined. Blowing out all the dust and snapping the shutter open on bulb, holding it up to the light. It looked gorgeous.

I loaded up another roll of HP5 and quickly worked through it. Impressed would be what I would say. The lens is really nice, it doesn’t blow me away, but I do like the rendering of older slow lenses and I love the absolutely tiny size of it. The images are good, they don’t make you swoon, but they do make you happy that you spent the time to use the camera. And when I say, ‘took the time’ I do mean that.

In a weird way, the cumbersome process of using the Retina 1a is what I love most about it. First, you have to open up the clamshell case, extract the lens, then I usually look at my hands for a few moments and think about how much I love holding well crafted objects. Then, I usually remember I have no idea how to use the Sunny 16 rule when I’m in the shade, and I pull out the meter on my iPhone. After taking a general reading of the approximate area I want to make an image of, I set the shutter and lens. Then, this is probably the best part, then you get to wind the film and charge the shutter.

With other cameras, like Nikons or Minoltas you’d instantly wind the film on and set the shutter. But, with a camera that won’t let you change to the fastest shutter speed after cocking the shutter you are better off waiting until you know what your image is going to be! The Retina 1a is one of those cameras – it goes all the way to 1/500th, which is nothing to sneeze at for 1951 – but you can only set it prior to charging the shutter.

Now is the moment you get to feel the little just-sharp-enough knurling on the film rapid winder, listening to the frame counter ratchet down, and feeling the film transport click away. It’s not the smoothest film transport, nor the most satisfying shutter to set – but there is something unique about the hand made practical nature of this affordable accessible old Kodak. It reminds me of the Contax IIa a little in this regard – simply a lovely object to handle and use.

Once your film is wound on, well now you just have to snap the shutter and you’re done! Oh, wait – unless you want to focus? How do you do that with a “view-finder” camera any way? Well, you could estimate – which I do quite a bit. Or, you could use an external rangefinder.

I pair my Retina 1a with a shockingly matchy-matchy Watameter rangefinder that I’ve owned for about 5 years, and it’s great. The Watameter has a nicely magnified viewer, and reads out in feet just like the Retina focus scale. I wish I could tell you that the camera view finder is a lovely thing to look through, but it’s not. It’s pretty small, tight, and cramped. This too reminds me of the Contax IIa.

So, what’s all the fuss? It’s a nice thing to hold in your hands. It’s a well thought out and well designed piece of machinery. It’s pretty. It makes nice images. It fits in your pocket. It reminds you that simple things can be the most fun.

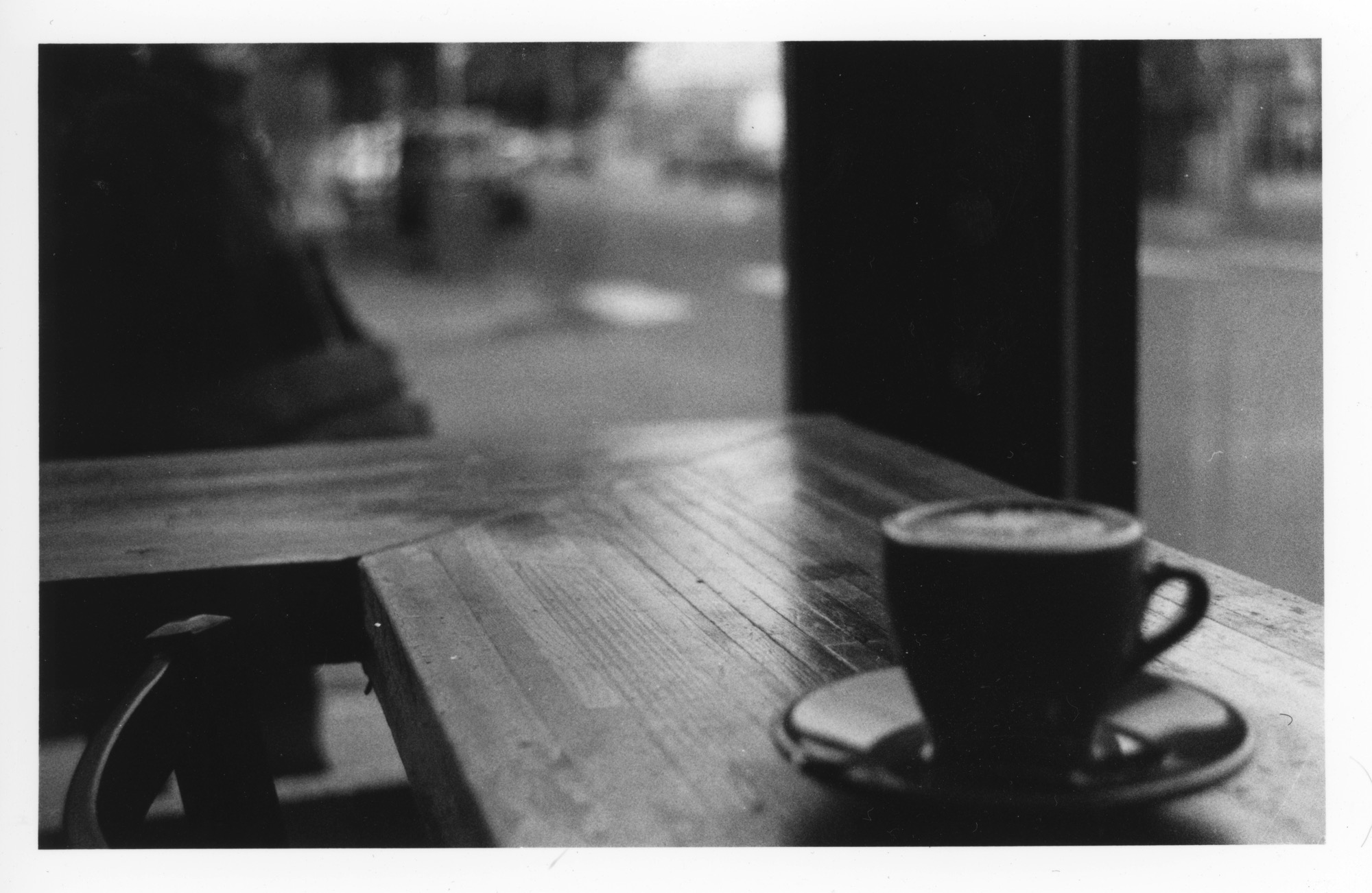

The images in the gallery below are all from the Retina 1a, they are from the last couple weeks around home, and a visit to Skamania Lodge in Washington. The film is mostly HP5 developed in HC-110b and Fomapan 200 developed in, gasp, DF96. There is generous use of under exposure in some of the images. Weirdly, I kind of like it. I like how dark they can be and still have texture. Maybe that’s part of getting older.

A pretty little camera, Fujica 35-ml

Fujica 35-ml rangefinder camera, a 35mm delight to use and a treat to look at.

The older I get, the more I love estate sales. I used to go to thrift shops almost every day. Recently, at least here in Portland, I've noticed what used to be thrift store finds are now housed in glass at vintage shops marked up 500%. Because of that, estate sales are my new love. This particular camera came from an estate sale.

The camera was in decent condition when I found it, but the shutter was stuck and I had to open it up to give it a slosh cleaning in order to shoot some test rolls. The rangefinder was a bit out of whack too, which might have been why it sat unused for so long. Thanks to smart Japanese engineering rangefinder adjustment screws are easily accessed from under the cold shoe.

Fuji made a ton of rangefinders over the years, with a bunch of different medium format versions from 6x4.5 up to 6x9. However, the Fujica rangefinder line was not immensely popular in the United States, so they fly under the radar a bit. From what I understand the 35mm rangefinders, especially weren't sold in great numbers in the U.S. so they are kind of a treat to find in good condition.

Oddities of the line: they all have the wind lever on the bottom, focus wheel on the back, and rewind on the side. All these things, are exactly what I love about it. This, surprisingly, isn't the only rangefinder camera I own with a focus wheel on the back. The Mamiya Six folder I have also operates the same way (although it moved the film plane instead of the lens). I really love being able to focus with just the move of my thumb, it feels much more natural on a rangefinder for some reason.

The little camera has a 45mm f2.8 lens that is nice and sharp, a characteristic of pretty much every Fuji lens it seems. It is essentially a small view camera lens, threaded into a leaf shutter. You set the shutter speed and aperture on the lens rings, just like you would on your large format rig. This is, more or less, the basic set up of all the Fuji / Fujica rangefinders - slap a traditional leaf shutter lens on the front of a body and make it focus.

Some of the shots that I got from the camera are really lovely.